The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

GASTON B MEANS

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Warren G Harding and Gaston Means

Excerpts from The Strange Death of Warren G Harding

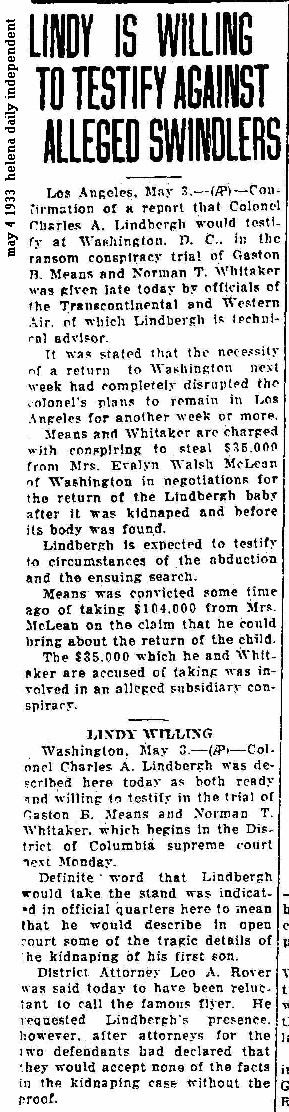

Norman T Whitaker cohort of Gaston Means suspected by the FBI of having been involved with Gaston in Lindbergh kidnap extortion scam.

MEANS v. UNITED STATES Appeal 1933

During the height of the publicity surrounding the supposed "kidnapping" many people, fraudulently claimed to have information about the baby. On March 4, 1932, Gaston B. Means, a con man, spoke with

Evelyn Walsh McLean.

McLean, enormously wealthy and the owner of the Hope Diamond, believed she could be some assistance to the Lindbergh family. Means assured her that he could get in contact with the "kidnappers" and claimed that he was even asked to help in the "kidnapping" weeks before. Means said that his friend was the person who took the Lindbergh baby from its crib. After claiming to have contacted the "kidnappers" he conned Mrs. McLean out of $100,000 to pay the ransom.

On April 17, 1932, when the child still had not been returned to it's family, McLean requested that her money be returned. Refusing to return the money, Means, along with Norman T. Whitaker, a disbarred Washington attorney, were taken into custody. Means was convicted of larceny and embezzlement, and sentenced to serve fifteen years in a Federal prison. Means and Whitaker were later convicted of conspiracy to defraud, and were sentenced to serve two years each in a Federal prison.

Later, McLean again offered her assistance. This time, not to bring home the baby - ( the body was already found) -, but to help Richard Hauptmann get an appeal and overturn his death sentence. The Hauptmann Defense Fund was running short of money and the defense team was beginning to lose hope. Without money, they could not continue their investigation. But a light of hope appeared with McLean. She believed that Hauptmann was not a lone killer. She offered to pay any fees so that the investigation could continue.

The defense had their eyes on Samuel Leibowitz - the best known criminal lawyer in New York. Leibowitz, defender of the Scottsboro Boys in 1926, had also been hired by gangster Al Capone for a triple-murder charge. In the end, Capone got off for the crimes.

Leibowitz said he would talk to Hauptmann. If he decided to take the case, he would need $10,000 for a retainer and $15,000 if he solved the crime. Leibowitz visited Hauptmann three times. He spent hours speaking with the accused. The only way to save Hauptmann, he said, was for him to confess. Hauptmann refused to "confess" and Leibowitz gave up the case. McLean was very upset that he quit.

No.

5802

Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia

62 App. D.C. 118; 65 F.2d 206; 1933 U.S. App.

Argued February 8, 1933 April 17, 1933, Decided

PRIOR HISTORY:

Appeal from the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia.

OPINION BY:MARTIN

OPINION:

[Before MARTIN, Chief Justice, and VAN ORSDEL, HITZ, and GRONER,

Associate Justices.

MARTIN, Chief Justice.

Appellant, defendant below, was convicted of the crime of larceny.

The indictment against him contained four counts. The first count charged

the larceny of $100,000 from Mrs. Evalyn Walsh McLean on March 7, 1932; the

third count charged the embezzlement from her of the same money; the second

count charged the larceny of $4,000 from Mrs. McLean on the 18th day of March

1932; and the fourth count charged the embezzlement of the same money.

Defendant pleaded not guilty. At the trial the court directed a verdict of

not guilty on the fourth count. The jury found the defendant not guilty on the

third count, but guilty on the first and second or larceny counts.

At the trial the defendant offered no testimony. The testimony of the

government convincingly established the following facts: That after the

kidnaping of the infant son of Colonel and Mrs. Charles A. Lindbergh on or

about the first day of March 1932, the defendant, in an interview with Mrs.

McLean, persuaded her by means of false [**2] and fraudulent statements that he

could assist in locating and recovering the kidnaped baby. Mrs. McLean was

induced by these representations to pay over to defendant the sum of $100,000

with which to pay the ransom and secure the return of the child. Upon a later

occasion defendant by similar means secured from Mrs. McLean the sum of $4,000

for the payment of alleged expenses of the kidnapers. These representations

made by defendant were willfully false and fraudulent and were designed solely

for the purpose of obtaining the money from Mrs. McLean and not for the purpose

of locating and recovering the child. The defendant converted the money thus

paid to him to his own use, and none of it was ever expended in an effort to

recover the child, nor was any part of it returned to Mrs. McLean.

It is contended by appellant that the lower court erred in refusing to

require the government to elect between the larceny and embezzlement counts of

the indictment before the submission of the case to the jury. This [*207]

contention is not sound. Section 361, title 6, of the D.C. Code, 1929,

provides: "Offenses that may be joined -- An indictment for larcenny may

contain

a count for [**3] obtaining the same property by false pretenses, a count for

embezzlement thereof, and a count for receiving or concealing the same property,

knowing it to be stolen or embezzled, or any of such counts, and the jury may

convict of any of such offenses, and may find any or all of the persons indicted

guilty of any of said offenses."

This section clearly contemplates the submission to the jury of all counts of

an indictment charging larceny and embezzlement of the same property; otherwise

the jury could not "convict of any of such offenses."

It is said by the court in Lorenz v. U.S., 24 App. D.C. 337: "Whether such

a

request should be granted depends upon the special circumstances of the case,

and rests in the sound discretion of the trial court." In Pointer v. U.S.,

151

U.S. 396, 14 S. Ct. 410, 412, 38 L. Ed. 208, the Supreme Court when passing on a

similar question said: "The court is invested with such discretion as

enables it

to do justice between the government and the accused."

In the instant case the same evidence was relied upon to support the larceny

and embezzlement counts. The determination of defendant's guilt or innocence

and of the nature of his offense depended upon [**4] the interpretation of that

evidence, and was a question of fact for the jury. It was submitted to the jury

in this case under proper instructions.

Appellant next contends that the lower court erred in overruling his motion

for a directed verdict upon the first and second counts of the indictment, being

the larceny counts. It is claimed by appellant that the testimony clearly

established a relationship of master and servant, or principal and agent,

between Mrs. McLean and appellant; that the money came into the possession of

appellant by virtue of this employment; and that, because of these circumstances

the crime, if any, was embezzlement and not larceny.

This contention is not tenable, for one who obtains money from another upon

the representation that he will perform certain service therewith for the

latter, intending at the time to convert the money, and actually converting it,

to his own use, is guilty of larceny ( People v. Martin, 116 Mich. 446, 74 N.W.

653; Grin v. Shine, 187 U.S. 181, 23 S. Ct. 98, 47 L. Ed. 130; People v.

Tomlinson, 102 Cal. 19, 36 P. 506; People v. Abbott, 53 Cal. 284, 31 Am. Rep.

59; Talbert v. U.S., 42 App. D.C. 1, certiorari denied 234 U.S. 762, 34 [**5]

S. Ct. 997, 58 L. Ed. 1581; People v. Shwartz, 43 Cal. App. 696, 185 P. 686;

Crum v. State, 148 Ind. 401, 47 N.E. 833; Martin v. State, 123 Ga. 478, 51 S.E.

334).

Appellant further urges that the court erred in permitting Mrs. McLean to

testify that appellant in his first conversation with her had told her of his

incarceration at a former period in the Atlanta Penitentiary. The record

discloses that Mrs. McLean, when testifying concerning this conversation, was

asked, "Was there anything said about where he had first made the

acquaintance

of this man?" To which she answered, "Yes; I remember he said the man

was in the

Atlanta Penitentiary with him." It is plain that this statement was not

brought

into the evidence for the purpose of reflecting upon appellant's reputation or

character, but was purely incidental to the testimony relating to the

conversation between the witness and appellant, which necessarily disclosed the

fact that appellant at one time had been an inmate in the Atlanta Penitentiary.

The evidence of other witnesses similarly introduced contained statements to the

effect that appellant had been in jail and in the penitentiary. It was not

error to admit competent [**6] evidence because of the fact that it

incidentally revealed that appellant had a criminal record. When the tendency

of testimony offered in a criminal case is to throw light upon a particular

fact, or to explain the conduct of a particular person, there is a certain

discretion on the part of the trial judge which a court of errors will not

interfere with, unless it manifestly appears that the testimony has no

legitimate bearing upon the question at issue, and is calculated to prejudice

the accused in the minds of the jurors. Moore v. United States, 150 U.S. 57, 14

S. Ct. 26, 37 L. Ed. 996. Therefore, this contention by appellant cannot be

sustained.

The judgment of the lower court is affirmed.

FROM

THE DIARIES OF GASTONS B.MEANS A Department of Justice Investigator

AS TOLD TO MAY DIXON THACKER Guild Publishing Corp., 1930

Preface

I first met Gaston B. Means in the Atlanta Penitentiary while making a study of prison conditions in the South. I was introduced to him by the Chaplain. I heard snatches of his story and was deeply interested. I felt at that time that he would be doing a real service to his country if he would, without dissimulation, tell his story to the world. This he has now done. The story is in no way a reflection on the American political system. On the contrary, it is a vindication of this system. It clearly reveals how a Great Party was tricked and how it has extricated itself with a dignity and poise and surety of purpose unexcelled in history. It was the human interest story, however,--not the political--point of view that impressed me most. That this human interest happened to focus on the White House and with the President and his wife made it all the more appealing and important. My treatment is a sympathetic one. The facts of the narrative belong to Gaston B. Means. I simply assembled these facts and put them in proper form. MAY DIXON THACKER.

Foreword

"IF GASTON MEANS should talk!"

I almost spoke the words aloud as I stepped my six foot, two hundred avoirdupois through the iron-grilled outer door of the Atlanta Penitentiary on the forenoon of the 19th day of July 1928, and breathed once again for the first time in three years the sweet clean pure air of God's outside world.

Although I am that much maligned individual-- Gaston Means, himself--I was at that moment conscious of viewing myself objectively, as a personality separate and apart. I was acutely conscious that this public malignment that had branded me before the world was the direct result of superdeveloped powers of dissimulation instilled and ingrained into me from early boyhood through a rigid life training as investigator and detective. For I had now to realize anew as I had been doing for many months in the close confines of prison walls,--that I, Gaston Means, was the only living human being who held accurate knowledge of dangerous truths concerning many social, political, financial and international secrets.

As I stood outside the door, I nodded a last farewell to the big guard stationed there, who manipulated so skillfully the soft click of the outer door lock and I threw back my head drinking in the first glories of a new free life. Then, suddenly, vividly, there passed before my mind in rapid tragic sequence--one by one--the ghostly procession of other persons who had known some of these secrets. There were in this procession: C. F. Cramer, Jess Smith, Lawyer Thurstons, John T. King, C. F. Hateley, Warren G. Harding,

Chapter

I

Mrs. Harding Employs Means as Private Detective

"MRS. HARDING wants me to come to the White House." This idea held a tenacious minor key in my consciousness all the time I was dispensing with the routine business at my desk in the Department of Justice, after the lunch hour at one o'clock on a late October day in 1921.

Buttoned securely in an inside coat pocket reposed a note that had been handed to me at eleven o'clock that morning. Shortly after ten o'clock, my phone had rung and I was told that the private secretary of a prominent man in Washington, Mr. Edward B. McLean, whose wife was a very special friend of Mrs. Harding--had a letter for me. And would I come to the lobby of the Shoreham Hotel right away? I had never met this secretary but he said that he would know me. I closed and locked my desk and went to the Shoreham Hotel. As I entered the lobby, I was met by a young man of perhaps thirty, with clear-cut features and faultlessly dressed. He said simply: "Mr. Means."

It was not a question but a statement, for he knew me. Then he took an addressed envelope from a pocket and handed it to me and said: "I am instructed to deliver this to you." I replied: "Thank you."No other word was spoken between us. I glanced at the envelope and saw that it was of the usual social stationery of the White House. In an upper left hand corner was engraved: "The White House." In the lower left hand corner was written: "Very personal and confidential." I recognized the handwriting of Mrs. Harding.

I put the letter in a pocket and returned to my desk at the Department of Justice I finished the work that was clamoring for attention before noon. I did not open the letter until I had found a secluded place free from interruption where I was entirely alone, during the lunch hour. The note thanked me for what I had done for her, and asked me to come to the White House at once--that she wanted to talk to me.

The note practically summoned me to the White House to see Mrs. Harding. It had been several weeks since I had been assigned to a very special piece of investigating for Mrs. Harding. To refresh my memory as to exactly how many days it had been,--I drew my diary from a pocket.

I have always kept a diary. It is an accurate record of every hour of my days and nights. This was part of a selfimposed rigid discipline as an Investigator. This diary has always been a valuable asset. If I want to know, for example, where I was and what I was doing on the 15th day of July, 1917,--all I have to do is to refer to my diary and I will find a detailed account of every hour of that day.

Glancing through the pages now--I saw that it had been three weeks and two days, since I had been working for Mrs. Harding. It had come about in this way.

William J. Burns who was at the head of the Investigation Bureau of the Department of Justice, sent for me to come to his office.5 My desk was on the first floor while his offices were on the seventh. Mr. Burns met me in an outer office, when I appeared in answer to his summons. He explained:

"Gaston--I have an important visitor in the office." He told me that it was General Sawyer--with a special mission from Mrs. Harding. It seems--that Mrs. Harding was a great believer in fortune tellers and soothsayers and stargazers and crystal gazers. I had heard rumors of this, just as everybody else in Washington. When President Harding was Senator, Mrs. Harding had gone with four other Senators' wives to consult a certain rather famous soothsayer--a Madam X. They were told by this prophetess at that time, that one of their husbands would one day be President. There was a public record of this occurrence in the newspapers.

After Mr. Harding was President, Mrs. Harding had gone on two occasions to the home of Madam X. She went ostensibly to have her fortune told. Mrs. Harding believed implicitly--so it was said--in this woman's supernatural powers of clairvoyance and divination. When the President learned of these visits--he was tipped off by a reporter as it was getting into the newspapers, he put a stop to them immediately.

A Sunday article appeared in one of the Washington papers about that time, telling the history of these magic arts,--laying the foundation for the story that Mrs. Harding was an ardent disciple. It was hinted that Mrs. Harding sincerely felt that the nation could not be properly run by the President without the aid of this soothsayer.

I had heard these things so I was not altogether unprepared for what Mr. Burns told me. It seems that when it became impossible for Mrs. Harding to either call at Madam X's home or have her come to the White House, she conceived the idea of writing questions that she wanted answered and sending them to Madam X by a special friend whom she had brought with her to Washington, a Mrs. Whiteley. * She put these questions in the form of a serial questionnaire. Mrs. Whiteley would carry the papers out to Madam X and she would keep them for several days,-dream over them, and then Mrs. Whiteley would call for them and take them back to Mrs. Harding, who would write new questions. I had never seen Mrs. Whiteley but knew her by reputation as a rather small brunette, always well and becomingly dressed: a vivacious and alluring personality. Mr. Burns told me that Mrs. Harding would sometimes speak of her as nurse, and then again as companion and I have heard her referred to as servant.

The serial questionnaire had been going back and forth carried by Mrs. Whiteley for some time. Many of these questions would be concerning matters of state,--of various appointments, of what Congress would do--or what the Senate should do in connection with certain important bills, and concerning judicial and diplomatic appointments and other executive and diplomatic appointments,--but also there were many questions of a most intimate character--about the President.

Mr. Burns told me--that this soothsayer in her zeal, had made a recent attempt to come to the White House and that this had been reported to the President. And he had such strong feelings in the matter and had expressed them to Mrs. Harding--that she had become alarmed about the serial questionnaire that contained her questions in her own handwriting and the answers in the handwriting of the soothsayer,--knowing that this paper was in the possession of Mrs. Whiteley. When she asked Mrs. Whiteley for it, she was told that it had been destroyed. But Mrs. Harding was not satisfied and had sent Gen. Sawyer to consult Mr. Burns. Mr. Burns briefly outlined the case to me, standing in the outer office. He told me that the matter was not to be known to anybody in the world but himself, myself, Gen. Sawyer and Mrs. Harding. "I'll introduce you to Gen. Sawyer," he said as we went into the inner office.

Sitting in this office, I saw a little, high-strung nervous man: highly polished and shining--shining face, shining shoes, shining glasses, shining buttons on his dapper uniform, shining false teeth--shining everything. At a glance, I had him catalogued according to my profession: a self-centered egotist.Mr. Burns spoke:

"Gen. Sawyer--this is Gaston Means. I can assure you that any matter that you take up with him in behalf of Mrs. Harding will be treated in the right way. In order--that you may know if there is a break anywhere down the line,--I'll not listen further to the story and I want you to tell it only to Gaston. He will let you know if what you want to accomplish can be done. I'll assign him personally--to handle it. It will not go further."

Mr. Burns left us alone. Gen. Sawyer began:

"I am an emissary from Mrs. Harding." Then he repeated the story that Mr. Burns had already told me and emphasized the very urgent need--that these most important papers in Mrs. Harding's handwriting and the answers in the handwriting of Madam X be recovered. All the questions had been answered--except the last serial of the questionnaire--that was pending. He concluded: "Do you think it's possible to get these papers?"

"Do you know the address of Mrs. Whiteley?" I asked.

"I can get it for you. I don't know it," was his reply.

"Can you also get the address of this soothsayer--Madam X?"

This address he gave me. The next remark of Gen. Sawyer gave me my first important dew. He said:

"Mrs. Whiteley says--the papers have been destroyed, you understand. . . . And whatever you do, do not annoy Madam X. She is a dangerous woman. She has unbelievable powers. I myself have consulted her many times. Why-- she can cast a spell over you! Whatever you do, don't antagonize her! These papers are not in her hands. If they have not been destroyed, Mrs. Whiteley has them."

He then entered into a long and technical and scientific dissertation about soothsayers and this amazing Madam X who could cast a spell. He spoke of her remarkable powers in delving into the subconscious mind--her clairvoyant gifts. I asked him--if he believed in witches and fortunetellers. He replied with great earnestness.

"Yes. There is much to it. It is as yet an unexplored field. As science advances--we will know that these extraordinary powers are--a connecting link between man and God. They are gifts, directly from God."

He was patronizingly patient with my ignorance and I tried to look intelligent. After he had further eulogized the soothsayer and reiterated many times his own absolute faith in her, I returned to the one important question: Mrs. Whiteley's address. He said he would send it to me privately-just on a card with no name. I gave him my home address. He gathered up his military cap, gloves and stick and papers, with little pecking movements and with the wiry strut of a bantam rooster, he went out. I remarked to Mr. Burns: "Is that man a nut--or what?"

He replied with a smile: "We are forced to deal with all sorts of people."

With the official assignment from Mr. Burns to Mrs. Harding, I began my investigation. I dictated a short note to Gen. Sawyer telling him to tell Mrs. Harding to arrange it diplomatically--that she would not need the services of Mrs. Whiteley until further notice. Mrs. Whiteley lived with her husband in an apartment in the city. I did not want my men to trail her to the White House. I could not have my agents hanging around there.

I took eight men in this surveillance:--"shadow" men.

WILLIAM

J. BURNS

Director

August 22, 1921 - June 14, 1924

William J. Burns was born around 1860 in Baltimore, Maryland, and educated in Columbus, Ohio. As a young man, Mr. Burns performed well as a Secret Service Agent and parleyed his reputation into the William J. Burns International Detective Agency. A combination of good casework and an instinct for publicity made Mr. Burns a national figure. His exploits made national news, the gossip columns of New York newspapers, and the pages of detective magazines, in which he published "true" crime stories based on his exploits. Well qualified to direct the Bureau, and friends with Warren Harding's Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty, Burns was appointed as Director of the Bureau of Investigation on August 22, 1921. Under Mr. Burns, the Bureau shrank from its 1920 high of 1,127 personnel to around 600 three years later. He resigned in 1924 at the request of Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone because of his role in the Teapot Dome Scandal. This scandal involved the secret leasing of naval oil reserve lands to private comanies.

Mr. Burns retired to Florida and published detective and mystery stories based on his long career for several years. He died in Sarasota, Florida, in April 1932.

Please visit :

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

ronelle@LindberghKidnappingHoax.com

![]() Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

© Copyright Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax 1998 - 2020