Directory Books Search Home Transcript Sources

by Judge W Dennis Duggan, JFC

reprinted from The Albany County Bar Association Newsletter

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

![]() Entire

Trial Transcript Now Available on CD ROM

Entire

Trial Transcript Now Available on CD ROM

February 11, 1935

The Prosecution was trying to say that Hauptmann alone planned and committed the crime. If the jury believed that the guilty party was a gang, and not Hauptmann alone, it should vote against the State of New Jersey.

The Prosecution, he said, wants the jury to think that Hauptmann was an intelligent man who plotted the kidnapping alone, but that he was dumb enough to spend an hour and a half talking with Dr. Condon. He was smart enough to not leave fingerprints at the Lindbergh estate, but he would openly spend Lindbergh ransom money.

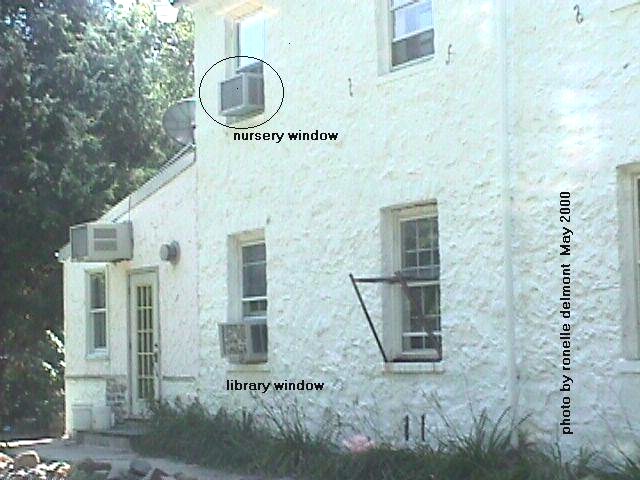

"The first thing you have got to decide when you go into your jury room is this: How in God's name did Hauptmann, in the Bronx, know anything about the Lindbergh home? Was that possible? No.

Colonel Lindbergh was stabbed in the back by the disloyalty of those who worked for him, and despite the fact that he courageously believes there was no disloyalty in the servants quarters, I say now that no one could get into that house unless the information was supplied by those who worked for the Colonel.

"What is the

evidence?

"What is the

evidence?

That the first time he spent a Tuesday night in that house was the Tuesday night of the kidnapping. Every other week end the family only stayed over Sunday night or early Monday morning.

Who knew the baby had a cold and had to stay in Hopewell on Monday? Not Hauptmann. Nobody but the Colonel, his lovely wife, his butler, his butler's wife, Betty Gow, the servants in the Morrow home and Red Johnson knew it. Betty Gow? The Colonel can have all the confidence he pleases in her. I have none. The butler?"

"There was one thing in that house that would only respond to its master and that was the little fox terrier- the snappiest, scrappiest dog alive, when it comes to a watchdog! And who controlled the dog's movements that night? The butler. I say the circumstances point absolutely along a straight line of guilt toward that butler and the disloyal servants. Can a man come up to a strange house with a ladder and stack it up against the wall and run up the ladder, push open a shutter and walk into a room that he has never been in before? That is what the State would have you believe!"

"The moment anyone put their hand on

that child, that child's cry ringing out would have brought the mother from her

bedroom close by. I will leave it to you mothers if I am not right! The person

who picked that child out of the crib knew that child- and the child knew that

person! Of course if instead of a physic, if the child had been doped, or given

paregoric or something- then the child wouldn't cry. But who gave the medicine?

Not Hauptmann. Who gave the physic? Not Hauptmann. And this little child is

picked up and they would have you believe that Hauptmann, who never saw the

child, never knew the child- and with a dog downstairs!- a strange man in the

house, and all the doors open!- they would have you believe that this stranger

to the house goes back with a twenty- or twenty-five pound child in his arms,

swings himself out of the window in the darkness and is able to find the top

rung of that ladder, three feet below the window shelf, that rickety old ladder,

and then, as he finds himself on the window seat and his feet touching the top

of the ladder, so that he can come down the ladder to the part where the dowel

pin joins it together, and then they say the dowel pin broke- but what they say

is not evidence."

"Remember the evidence of the officer who found the ladder fifty to seventy-five feet away from the house! Remember the mud between the house and the ladder! You can't walk in mud without leaving footprints, can you? But there was not a footprint between the house and the ladder! Why?"

"I say that ladder was a plant. I say that ladder was never up against the side of the house that night. Now am I right in saying that you have a right to assume this evidence that somebody disloyal to the Colonel entered the nursery, somebody who knew that baby?"

"Oh, it was so well planned by disloyal people! So well planned!"

Reilly then spoke about the location of everyone on March 1. Oliver Whately was downstairs. Elsie Whately and Betty Gow were talking about a dress. And the Colonel and his wife are eating dinner, secure in the belief that they are safe. They are out of sight of the front door and out of sight of the rear door. And all of the sudden comes the signal - 'The coast is clear; they are at dinner.'

The signal? The telephone call from Red Johnson, whom Betty Gow had left only two hours before."

"Who is hiding things here? Who is hiding the truth?"

Then Reilly spoke about how New Jersey spent lots of money bringing Isidor Fisch's family to America. And why? Only one of Fisch's relatives testified at the trial. Yet, New Jersey never even tried to bring Red Johnson back from Norway, he noted. Reilly continued telling the story of March 1.

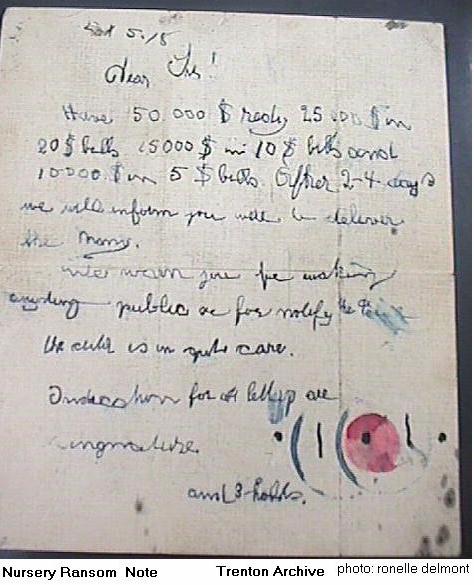

"Opinion evidence means that this man says, 'I think it is this.' Another man says, 'I think it is that.' And the wise courts and judges have decided for many years that a jury has a perfect right to disregard expert evidence altogether and use their own common sense. It is very important for the prosecution to try and pin this nursery note on Hauptmann- that is part of what I call their scenario. But I ask you this, please: before finding that this is Hauptmann's handwriting- if you ever do, because he has denied it- please keep in mind that there is no evidence except this produced by the prosecution which puts Hauptmann in the nursery March the first, and this note places him there through the opinion, or guesswork, we will call it, of

Mr. Osborn and those who

followed him."

Reilly claimed that everyone had said the handwriting was disguised so how could they tell? He then continued to speak, now mentioning the thought of gang involvement. He began speaking of Dr. Condon.

"Dr. Condon stands behind something in this case that is unholy." He was quick to defend Red Johnson, Reilly mentioned. Why? Were they, together, involved with the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby. Reilly then speculated about Dr. Condon. Everything he did, he did "Alone, alone, alone!"

The last statement then turned to Violet Sharp.

Why did she kill herself?

"... Violet had let something drop, had given a clue. And suddenly the detectives came back and said, 'Bring Violet down here again.' Inspector Walsh and his detectives have checked up and found something- and Violet knows it. And she drains the poison. Why? Not because she was afraid about her job. She did it because the woman from Yonkers, Mrs. Bonesteel, told the truth. Sommer too. Violet was at the ferry to Alpine with a blanket and later at Forty-second Street with a child in a blanket, and that child was the Colonel's child, and while I have the greatest respect for the distinguished Mrs. Morrow, I believe she is honestly mistaken. I don't think Mrs. Morrow remembers correctly that she saw Violet at eleven or twelve that night, because it just doesn't fit in with Violet's suicide."

He continued to speak about Violet Sharpe and her possible connection. Then, he moved on to Fisch.

"Not a dollar of that money, of that ransom money, ever went through Wall Street or went through a bank! One bank might slip up. But there was a bank in Mount Vernon. There was the Central Savings Bank. There was the bank the brokers did business with. There were three or more banks, and there were those brokerage accounts, and not a brokerage account and not a bank account found a dollar of this money!"

Then, Reilly spoke of the ransom notes - about how Hauptmann was dictated to write and spell the note. He reminded the jury that Hauptmann said, "I wrote as I was told to write. They spelled words for me and I spelled those words as I was told to write. They spelled words for me and I spelled those words as they told me to."

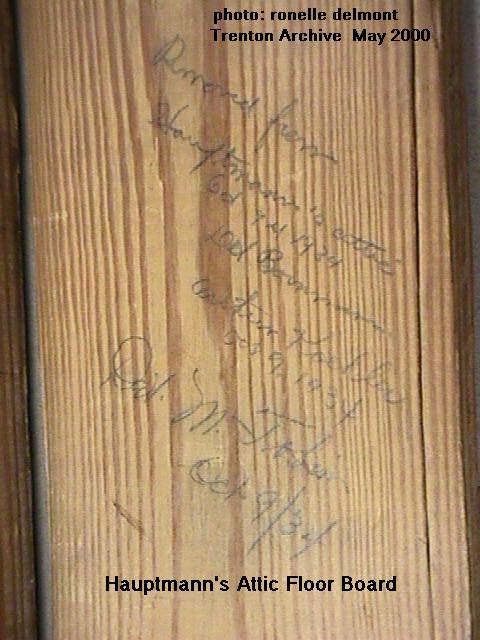

"Of all the crooked evidence in this

case, of all the plants that were ever put into a case, this board on the inside

of a closet - where they would have you believe a man would crawl in, crawl into

that dark closet, and over in a corner on a board write Dr. Condon's number as

it was three or four years ago- this board is the worst example of police

crookedness that I have ever seen."

"Do you suppose the board used in the ladder was ever taken out of any attic floor? Examine it carefully! It doesn't bear a mark from any hammer. But Mr. Koehler comes in- and here we are again with expert evidence as opposed to horse-sense- and he'd have you believe that this carpenter, Hauptmann, who could buy any kind of wood in a lumberyard, went out and got two or three different kinds of wood, and then said to himself, 'My goodness, I am short a piece of lumber! What am I going to do?'"

"Whatever was he going to do? There is a lumberyard around the corner. And so he crawls up into his attic and tears up a board and takes it downstairs and saws it lengthwise and crosswise and every other wise to make the side of a ladder!"

"You men on the jury have handled boards. Down in the Carolinas billions and billions of board feet are produced every year, and yet Koehler has the nerve to tell us that there never were two boards alike in all those billions of feet!"

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the case is too perfect from the prosecution's point of view and what they produced here. There isn't a man in the world with brains enough to plan this kidnapping alone and not with a gang and then sit down and make the foolish mistake of ripping a board out of his attic and leaving the other half of it there!"

"I believe Richard Hauptmann is absolutely innocent of murder. And I feel sure that even Colonel Lindbergh wouldn't expect you and doesn't expect you to do anything but your duty under the law and under the evidence."

"May I say to him, in closing, that he has my profound respect. I feel sorry for him in his deep grief, and I am quite sure that all of you agree with me that his lovely son is now within the gates of Heaven."

THE PROSECUTION: David Wilentz

"'Judge not lest ye be judged,' my adversary says. But he forgets the other Biblical admonition:

"' And he that killeth any man shall surely be killed, shall surely be put to death.'"

"For all these months since October 1934, not during one has there been anything that has come to light that has indicated anything but the guilt of Bruno Richard Hauptmann. Every avenue of evidence leads to the same door: Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

"What type of man would murder the child of Charles and Anne Lindbergh? He wouldn't be an American.

No American gangster ever sank to the level of killing babies. Ah, no! An American gangster that did want to participate in a kidnapping wouldn't pick out Colonel Lindbergh. There are many people much wealthier than the Colonel. No; it had to be a fellow who had ice water, not blood, in his veins. It had to be a fellow who had a peculiar mental makeup, who thought he was bigger than Lindy- a fellow who, when news of the crime came out, could look at the headlines screaming across the page, just as the headlines screamed when Lindy made his famous flight. It had to be an egomaniac, who thought he was omnipotent."

"And let me tell you, men and women of the jury, the State of New Jersey and the State of New York and the federal authorities have found an animal lower than the lowest form in the animal kingdom, Public Enemy Number One of this world- Bruno Richard Hauptmann!"

Then, Wilentz spoke of the decent people who testified honestly in court- Dr. Condon, Colonel Schwarzkopf, Arthur Koehler, Betty Gow. The list went on.Wilentz mentioned how Betty Gow was so much for justice and for helping to punish the guilty party that she returned from Scotland.

"Contrast that with Hauptmann, over in the Bronx. Boy! When he heard the State of New Jersey wanted him, did he say, 'I'll come right over?"

The Attorney General then spoke of the Prosecution's version of March 1. He then countered Reilly's accusation that the baby did not cry because he knew the person who took him from his crib:

"I don't think that's a fair statement of fact, men and women of the jury. I think a stranger could walk into a child's room, if the child were asleep, without the child awakening."

"But let me tell you this! This fellow took no chance on the child awakening. He crushed that child right in the room, into insensibility. He smothered and choked that child right in that room. That child never cried, never gave any outcry, certainly not! The little voice was stilled right in that room. He wasn't interested in the child. Life meant nothing to him. That's the type of man we're dealing with."

"Public Enemy Number One of the world! That's what we're dealing with! You're not dealing with a fellow who doesn't know what he's doing. Take a look at him as he sits there! Look at him when he walks out of this room today- panther like, gloating, feeling good!"

"Certainly he stilled this little child's breath. Right in that room! That child didn't cry out when it was disturbed. Yanked from the crib- how? Not just taken up; the pins were still left in the bed sheets. Yanked, and its head hit up against the headboard- must have been hit. He couldn't' do it any other way. Certainly it must have hit up against that board. Still no outcry. Why? Because there was no cry left in the child. Did he use the chisel to crush the skull at the time or to knock it into insensibility? Is that a fair inference? What else was the chisel there for? To knock that child into insensibility right there in that room."

Wilentz continued speaking- of how the evidence of the Defense Team was all circumstantial. He reviewed the Prosecution's evidence, claiming it was the true evidence. He continued:

"And the note in the nursery. This fellow had planned this crime. He wasn't going to let any faker come in and take the money. He had something on that note so that Colonel Lindbergh could tell, if another one came, that it was from the right party. So he put his signature on it. You couldn't reproduce it. The blue circles, the red center and the holes- b in blue, for Bruno; r in red, for Richard; holes, h for Hauptmann!"

He then repeated the last statement, pronouncing signature as singnature- the way John had pronounced it when speaking with Dr. Condon on the telephone.

"Now, men and women of the jury, take those writings Hauptmann made in the police station. Go through every one of them and you won't find the word signature anywhere. He was never asked to write it, right or wrong! And still he swears on the witness stand that he was told by the police to misspell it!"

"Mr. Reilly says the case is too perfect. No case can be too perfect, but it is perfect- perfect because of Hauptmann's conduct. Every piece of evidence we have he presented to us."

"There are some cases in which a recommendation of mercy might do- but not this one, not this one! Either this man is the filthiest and vilest snake that ever crept through the grass or he is entitled to an acquittal. And if you believe as we do, you have got to convict him. If you bring a recommendation of mercy, a wishy-washy decision, that is your province, and once I sit down I will not say another word, so far as this jury and its verdict is concerned. But it seems to me you will have the courage to find Richard Hauptmann guilty of murder in the first degree."

Many found it quite odd that Wilentz changed his theory from the beginning of the trial when he gave his opening statement. In his opening remarks, he claimed the baby died when the kidnapper dropped him down the ladder. He made it seem like an accidental death which occurred during the theft of the child.

In his closing argument, however, Wilentz did a 180 degree turnaround and painted a picture of a despicable man who murdered a sleeping baby in its crib and later, carried its dead body with him until discarding it in the woods. This new story, completely unmentioned during the entire trial and only raised in Wilentz' closing argument, seemed to cover the question of : Why did the baby NOT cry out while going down the ladder?

It also made an emotional demand for the death sentence more effective upon the horrified jurors.

The Interruption: Vincent Burns

Attorney General Wilentz finished his closing remarks when a man stood up. He said, "I have a confession that was made to me by a man who committed this crime -" Guards were on him, covered his mouth with their hands, and took him out of the courtroom. This was cause for mistrial.

The lawyers were called to the bench. Reilly said he knew the man to be Vincent Burns, a pastor. He said Burns came to him before and told him that Hauptmann was innocent, that the real killer confessed to him on Palm Sunday in 1932. He, however, felt that Burns was insane. The others agreed.

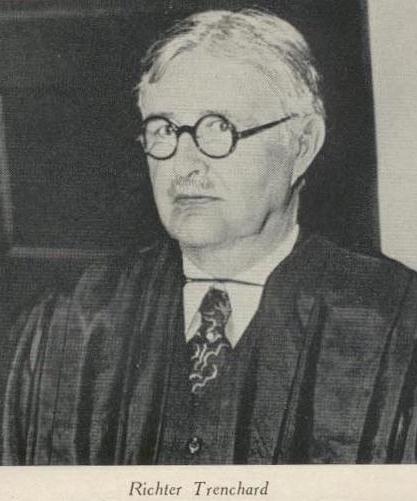

Judge Trenchard said to the jury: "It is very unfortunate that this scene had to occur but I don't imagine you heard anything except the man's first words. But if you did hear anything more, my instruction to you is that you utterly and entirely disregard it and forget the scene."

"Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the prisoner at the bar, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, stands charged in this indictment with the murder of Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., in this county on the first day of March, 1932. It now becomes your duty to render a verdict upon the question of his guilt or his innocence and upon the degree of his guilty, if guilty. In doing this you must be guided by the principles of law bearing upon the case that I will now proceed to lay before you."

"In the determination of all questions of fact, the sole responsibility is with the jury. You are the sole judges of the evidence, of the weight of the evidence, and of the credibility of the witnesses. Any comments that I may make upon the evidence will be made not for the purpose of controlling you in your view of the facts but only to aid you in applying the principles of law to the facts as you may find them. You must not consider what I shall say concerning the evidence as being accurate, but you must depend upon your own recollection. You must not only consider the evidence to which I shall refer, but you must consider all of the evidence in the case."

"in this, as in every criminal case, the defendant is presumed to be innocent, which presumption continues until he is proven to be guilty. To support the indictment and to justify a conviction, the State must prove the facts sufficient for that purpose by evidence beyond a reasonable doubt; and that burden never shifts from the State. If there be reasonable doubt whether the defendant be guilty, he is to be declared not guilty."

"Reasonable doubt is a term often used but not easily defined. It is not a mere possible doubt. It is that state of the case which, after the entire comparison and consideration of all of the evidence, leaves the minds of the jurors in that condition that they cannot say that they feel an abiding conviction to a moral certainty of the truth of the charge. The evidence must establish the truth of the fact to a moral certainty, a certainty that convinces and directs the understanding and satisfies the reason and judgment of those who are bound to act conscientiously upon it."

"But if, after canvassing carefully the evidence, giving the accused the benefit of reasonable doubt, you are led to the conclusion that the defendant is guilty, you should so declare by your verdict."

"To make out a case of guilt the State must establish by evidence beyond a reasonable doubt, first, the death of Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., as a result of a felonious stroke inflicted on the first day of March, 1932, in this county. To support that charge, the State has produced evidence to the following effect. The fact of death seems to be proved, and admitted. On the evening of March first, the child was prepared for bed by its mother and its nurse, Betty Gow, at the Lindbergh home in this county. The evidence is to the effect that the child was then in good health, a normal child except for a slight cold; that the mother and the nurse securely fixed the covering about the child, and about eight o'clock closed the window and left the room; that between that hour and ten o'clock the window was removed from the bed by some person and carried away, with the clothing in which it had been put to bed."

"There is evidence from which you may conclude, if you see fit, that the person who carried away the child entered the nursery through the southeast window by means of a ladder placed against the side of the house, under or near the window, and that this occurred shortly after nine o'clock."

"You will recall the evidence of Colonel Lindbergh to the effect that, as he was sitting in his living room downstairs, he heard a strange noise about that time, the sound of wood, like the striking of two pieces of wood together, like the boards of a crate falling off of a stand or chair. He testified that he could not tell where the sound came from, and at the moment he did not think much about it. Later, at about ten o'clock, when the disappearance of the child became known, a strange and broken ladder was found, about sixty or seventy feet from the southeast window, with indications that it had been used in entering and leaving the window; and also there were the imprints of a man's shoe in the soft ground under or near the window."

"Miss Gow and Mrs. Whately testified that later, about April first, 1932, they found the thumb guard, which Miss Gow had securely tied to the wrist of the child's sleeping suit when she put him to bed, that they found this thumb guard in the road leading from the Lindbergh home and on the Lindbergh property, with the knot still untied, from which you may possibly conclude that the sleeping suit was slipped off of the child at that place."

"There is also evidence to the effect that there was a dirty smudge on the floor of the nursery, leading from the window to the child's crib, and a ransom letter left on the window sill. Later, the child's dead and decomposed body was found in a shallow grave, not far from the road, a few miles away, in Mercer County."

"Dr. Mitchell, who performed the autopsy, testified that the child died of a fractured skull, the result of external violence. It was a very extensive fracture. He further testified that, in his opinion, death occurred either instantaneously or within a very few minutes following the actual fractural occurrence. It is the contention of the State that the fracture described by Dr. Mitchell was inflicted upon the child when it was seized and carried out of the nursery window down the ladder and when the ladder broke."

"Now, the ladder has been placed in evidence. Its broken condition when found in the yard has been described to you."

"The fact that the child's body was found in Mercer County raises a presumption that the death occurred there; but that, of course, is a rebuttable presumption, and may be overcome by circumstantial evidence. In the present case the State contends that the uncontradicted evidence of Colonel Lindbergh and Dr. Mitchell, and other evidence, justifies the reasonable inference that the felonious stroke occurred in Hunterdon County, when the child was seized and carried out of the nursery window and down from the ladder by the defendant, and that death was instantaneous; and from the evidence you may conclude, if you see fit, that the child was feloniously stricken on the first day of March, 1932, in this county, and died as a result of that stroke."

"Secondly, the State, in order to justify a verdict of guilty, must establish by the evidence, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the death was caused by the act of the defendant. The uncontradicted evidence is that the child was left by the mother and the nurse in the nursery, and the window was then closed. The evidence justifies the inference, if you see fit to draw it, that the window was maliciously opened and the child seized shortly after nine o'clock that night. You will, of course, recall the evidence to the effect that almost immediately after it was discovered that the child had been taken from its crib, there was found the ransom letter, demanding fifty thousand dollars, on the window sill, on which was placed a peculiar symbol and peculiar punch holes, and stating that directions would later be given for the delivery of the money. There is also evidence to the effect that a few days later Colonel Lindbergh received a second letter with like symbols, referring to the original ransom letter, an reiterating that directions for the delivery of the ransom money would be given. Meanwhile, Colonel Breckinridge, the friend and counselor of Colonel Lindbergh, had identified himself with the case in an endeavor to help his friend."

"There is evidence to the effect that a few days before March ninth, 1932, Dr. Condon had inserted an advertisement in the Bronx newspaper in effect offering to act as a go-between;

that a few days later Dr. Condon received a letter accepting his offer and enclosing a letter to Colonel Lindbergh, telling Dr. Condon that after he got the money to put words in the New York American that the money is ready, and the letter to Colonel Lindbergh said Condon may act as go-between, to give him the money, with directions as to the package; and how thereafter the baby was to be found."

"This letter to Colonel Lindbergh, as I recall the testimony, contained the peculiar symbols of the original ransom letter. The evidence is to the effect that immediately Dr. Condon drove to Hopewell and conferred with Colonel Lindbergh and with Colonel Breckinridge and, with their acquiescence, he inserted the advertisement, 'I accept; money is ready.'"

"Dr. Condon testified that shortly thereafter he received a letter addressed to him, and delivered to him by a taxicab driver, giving him instructions how to proceed. The taxicab driver testified that he was given that letter by the defendant Hauptmann. Dr. Condon testified that, as a result of the directions contained in that letter and another letter, he first had, on March twelfth, 1932, an interview in Woodlawn Cemetery with a man whom he identifies as the defendant, after talking with him more than an hour. In the interview Dr. Condon said that the defendant, after having run away from the gate, said, among other thing, 'It is too dangerous. Might be twenty years or burn. Would I burn if the baby is dead?'"

"Dr. Condon also testified in effect that the defendant said that the baby was being held on a boat by others, that 'We are the right parties,' that the baby was held in the crib by safety pins, and he said he would send the sleeping suit. Dr. Condon further testified that later he received the sleeping suit, and other letters containing further directions, and finally a letter directing that the money be ready by Saturday night and to put an advertisement in the newspaper, 'Everything O.K.' and that these directions were complied with by him, Condon, with the acquiescence of Colonel Lindbergh and Colonel Breckinridge, the latter of whom had been in close touch with Dr. Condon during practically the whole of the ransom negotiations."

"There is testimony to the effect that on this Saturday night, April second, 1932, there was delivered to Dr. Condon's residence a letter containing further instructions, and that as a result thereof on that evening Colonel Lindbergh, who was there waiting, drove Dr. Condon to the entrance to St. Raymond's Cemetery with the ransom money; that Dr. Condon alighted and contacted with a man, and after some talk and some delay handed him the package containing fifty thousand dollars of ransom money, thirty-five thousand dollars of which was in gold certificates, the numbers of which bills had been taken."

"It is argued that Dr. Condon's testimony is inherently improbably and should be in part rejected by you, but you will observe that his testimony is corroborated in large part by several witnesses whose credibility has not been impeached in any manner whatsoever. Of course, if there is in the minds of the jury a reasonable doubt as to the truth of any testimony, such testimony should be rejected; but, upon the whole, is there any doubt in your mind as to the reliability of Dr. Condon's testimony?"

"There is evidence to the effect that after Dr. Condon alighted with the money he was hailed by a man on the other side of the hedge, to whom he finally delivered the ransom money. Colonel Lindbergh testified that the voice that hailed Condon was that of the defendant. Dr. Condon testified that the man to whom he delivered the money was the defendant. This is denied by the defendant, and there is other testimony bearing upon the matter, and so that question becomes one for your determination."

"It is argued that Colonel Lindbergh could not have identified that voice, and that it is unlikely that the defendant would have talked with Condon. Well, those questions are for the determination of this jury, after having patiently listened to the evidence bearing upon those topics. If you find that the defendant was the man to whom the ransom money was delivered, as a result of the directions in the ransom notes, bearing symbols like those on the original ransom note, the question is pertinent: Was not the defendant the man who left the ransom note on the window sill of the nursery, and who took the child from its crib, after opening the closed window?"

"It is argued by the defendant's counsel that the kidnapping and murder was done by a gang, and not by the defendant, and that the defendant was in nowise concerned therein. The argument was to the effect that it was done by a gang, with the help or connivance of some one or more servants of the Lindbergh or Morrow households."

"Now do you believe that? Is there any evidence in this case whatsoever to support any such conclusion?"

"A very important question in the case is, Did the defendant Hauptmann write the original ransom note found on the window sill, and the other ransom notes which followed? Numerous experts in handwriting have testified, after exhaustive examination of the ransom letters, and comparison with genuine writing of the defendant, that the defendant Hauptmann wrote every one of the ransom notes, and Mr. Osborn said that that conclusion was irresistible, unanswerable and overwhelming. On the other hand, the defendant denies that he wrote them, and a handwriting expert, called by him, so testified. And so the fact becomes one for your determination. The weight of the evidence to prove genuineness of handwriting is wholly for the jury."

"As bearing upon the question whether or not the defendant was the man to whom was paid the ransom money in the cemetery, you will, of course, consider the evidence to the effect that the defendant had written the address and telephone number of Dr. Condon on the door jamb of his closet; and if you believe that he did, although he now denies it, you may conclude that it throws light upon the question whether or not he was dealing with Dr. Condon. As I have said, the defendant denies that he was the man who was paid the ransom money, and there is other testimony which, if credible and believed by you, supports his statement."

"You will consider, as bearing upon that question, the fact that a record of the serial numbers of the ransom money was retained. Now, does in not appear that many of the ransom bills were traced to the possession of the defendant? Does it not appear that many thousands of dollars of ransom bills were found in his garage, hidden in the walls or under the floor, that others were found on his person when he was arrested, and others passed by him from time to time?"

"You may also consider in this connection the evidence to the effect that shortly after the delivery of the ransom money the defendant began to purchase stocks in a much larger way and to spend money more freely than he had before."

"The defendant says that these ransom bills, monies, were left with him by one Fisch, a man now dead."

"Do you believe that? He said that he found them in a shoe box which had been reposing on the top shelf of his closet several months after the box had been left with him, and that he then, in the garage, where they were found by the police. Do you believe his testimony that the money was left with him in a shoe box, and that it rested on the top shelf in his closet for several months? His wife, as I recall it, said that she never saw the box; and I do not recall that any witness excepting the defendant testified that they ever saw the shoe box there."

"As bearing upon the question whether or not the defendant was the man who took the child and left the ransom letter on the window sill, you should, of course, consider the evidence with respect to the ladder, if you find, as seems likely, that it was used in reaching the nursery. That the ladder was there seems to be unquestioned. If it was not there for the purpose of reaching nursery window, for what purpose was it there? There is evidence from which you may conclude, if you see fit, that the defendant built the ladder, although he denies it. Does not the evidence satisfy you that at least a part of the wood from which the ladder was built came out of the flooring of the attic of the defendant?"

"In this connection you should consider the marks upon the wood, and give the evidence in respect thereto such weight as you think it entitled to, after a consideration of the credibility of the witnesses who testified in respect thereto."

"The defendant has offered himself as a witness in his own behalf, and the law makes him a competent witness, notwithstanding his very deep interest in the event of the trial. His evidence is not to be rejected merely for the reason that the is interested, but his interest in the result may be taken into consideration by you as an important circumstance upon the question of his credibility, the question whether he s telling the truth. You should also consider his testimony in view of its inherent probability or improbability, in the light of all the facts and circumstances as disclosed by the evidence. It appeared on the examination of the defendant here in court that he has been heretofore convicted of crime. That testimony may be given consideration by you as affecting his credit as a witness, and for that purpose only. The defendant denies that he was ever on the Lindbergh premises, denies that he was present at the time the child was seized and carried away. He testifies that he was in New York at the time. He denies that he received the ransom money in the cemetery and says that he was at his home at that time on the evening of April second, 1932."

"This mode of meeting a charge of crime is commonly called setting up an alibi. It is not looked upon with any disfavor in the law, for, whatever evidence tends to prove that the defendant was elsewhere at the time the crime was committed by the defendant, whereas here, the presence of the defendant is essential to guilt, and if a reasonable doubt of guilt is raised, even by inconclusive evidence of an alibi, the defendant is entitled to the benefit of that doubt."

"As bearing upon the question of whether or not the defendant was present at the Lindbergh home on March first, 1932, you, of course, should consider the testimony of Mr. Hochmuth, along with that of other witnesses. Mr. Hochmuth lives at or about the entrance of the lane that goes up to the Lindbergh house."

"He testified that on the forenoon of that day, March first, 1932, he saw the defendant at that point, driving rapidly from the direction of Hopewell; that he got in the ditch or dangerously near the ditch; and that he had a ladder in the car, which car was a dirty green. This testimony, if true, is highly significant. Do you think that there is any reason, upon the whole, to doubt the truth of the old man's testimony? May he not have well and easily remembered the circumstance, in view of the fact that that very night the child was carried away? The defendant, as I have said, denies that he was there or even in the neighborhood; but, as bearing upon that question, you should consider the testimony of other witnesses, that the defendant was seen in the neighborhood, not long before March first, 1932, and give it such weight as you think it is entitled to, after considering the credibility of the witnesses, as disclosed by the evidence."

"The defendant has produced some testimony besides his own, that he was in New York on the day and evening of March first, 1932, and some testimony besides his own, that on the evening of April second, 1932, when the ransom money was delivered, he was at his home."

"This testimony produced by the defendant I shall not attempt to recite in greater detail. It should be given consideration by you and given such weight as you think it is entitled to, after considering it in connection with all of the other questions in the case, determination of which would tend to throw light upon the case."

"You should consider the fact, where it is the fact, that several of the witnesses have been convicted of crime, and to determine whether or not their credibility has been affected thereby; and where it appears that witnesses have made contradictory statements, you should consider that fact and determine their credibility as affected thereby."

"The evidence produced by the State is largely circumstantial in character. In order to justify the conviction of the defendant upon circumstantial concur to show that he committed the crime charged, but that they are inconsistent with any other rational conclusion."

"It is not sufficient that the circumstances proved coincide with, account for and therefore render probable the hypothesis that is sought to be established by the prosecution. They must exclude to a moral certainty every other hypothesis but the single one of guilt, and if they do not do this, the jury should find the defendant not guilty."

"And when the case against the defendant is made up wholly of a chain of circumstances, and there is reasonable doubt as to any fact the existence of which is essential to establish guilty, the defendant should be acquitted."

"But the crime of murder is not one which is always committed in the presence of witnesses, and if not so committed, it must be establish by circumstantial evidence or not at al. And where the essential facts and circumstances are proved, which cannot be explained upon any other theory that that the defendant is guilty of the crime charged against him, such evidence should be considered as satisfactory and convincing as that of the most direct and positive character."

"If the State has not satisfied you by evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the death of the child was caused by the act of the defendant, he must be acquitted. But if, on the other hand, the State has satisfied you beyond a reasonable doubt that the child's death was caused by the unlawful and criminal act of the defendant while seizing, stealing and carrying away the child and its clothing, of which unlawful act against the peace of the State, the probably consequences might be bloodsheet, it is murder; and if murder, the degree thereof must then be determined."

"Now, our statue declares, among other things:"

"Murder, which shall be committed in perpetrating, or attempting to perpetrate any burglary, shall be murder in the first degree."

"I charge you that if murder was committed in perpetrating a burglary, it is murder in the first degree, without reference to the further charge you, as requested by the defendant, that in order to convict this defendant you must be satisfied, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the death of the child ensued from committing, or attempting to commit, burglary, at or about the time and place in question."

"Our statue relating to burglary says:"

"Any person who shall, but night, willfully or maliciously break and enter any dwelling house with intent to steal, commit a battery, shall be guilty of a high misdemeanor."

"If, therefore, the defendant by night willfully and maliciously broke and entered the Lindbergh dwelling house with intent to steal the child and its clothing and to commit a battery on the child, he committed a burglary; and if the murder was committed in perpetrating a burglary, it is murder in the first degree."

"In the circumstance of this case you must be satisfied that the window was shut and that it was raised and opening by the defendant, and that he entered the house."

"There is evidence from which you may conclude, if you see fit that the defendant feloniously, willfully and maliciously broke and entered the dwelling house of Colonel Lindbergh in the night time with intent to steal the child and its clothing and commit a battery upon the child; that the defendant brought the ladder to the Lindbergh house in East Amwell Township in this county, and placed it up against the house near the nursery window; that shortly after nine o'clock at night he ascended the ladder, maliciously and willfully opened the closed window and entered the nursery room; that he seized the child and its clothing and carried it out of the nursery room window, and that the fracture of the skull which caused the child's death was inflicted when the child was seized by the defendant and carried out and down the ladder, and when the ladder broke."

"If you find that the murder was committed by the defendant in perpetrating a burglary, it is murder in the first degree, even though the killing was unintentional."

"If there is a reasonable doubt that the murder was committed by the defendant in perpetrating a burglary, he must be acquitted."

"I am requested to charge, and do charge, that each juror must reach his own judgment after discussion of the facts with his fellow jurors."

"If you find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree, you may, if you see fit, by your verdict, and as a part thereof, recommend imprisonment at hard labor for life."

"If you should return a verdict of murder in the first degree and nothing else, the punishment which would be inflicted on the verdict would be death."

"If you desire to return a verdict of murder in the first degree, coupled with imprisonment for life, then you must so put it in your verdict, because the law reads that every person convicted of murder in the first degree, his aiders, abettors, counselors and procurers, shall suffer death unless the jury shall, by their verdict and as a part thereof, upon and after consideration of all the evidence, recommend imprisonment at hard labor for life, in which case this is no greater punishment shall be imposed."

Please visit :

![]() Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

Lindbergh

Kidnapping Hoax Forum

![]() Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

Ronelle Delmont's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax

You Tube Channel

ronelle@LindberghKidnappingHoax.com

![]() Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

Michael

Melsky's

Lindbergh Kidnapping Discussion Board

© Copyright Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax 1998 - 2020